Happy Birthday, Shakespeare?

For those of you who still believe…

In glad commemoration of that day

On which the life of Avon’s Bard began?

I proffer here suggestions, if I may…Perhaps a lay in shrill falsetto sung

By minstrel gay, in pied velour bedecked?

Or fool’s gold nuggets, dull, but neatly strung?

Or wax bananas, true-to-life, correct?

Perhaps a powdered wig, some nice perukes?

From Fred’rick’s store in Hollywood, perchance,

A pair of fake, yet sassy, maxi-glutes

One’s nonexistent tush made to enhance?

No book of Ossian, bust of Ba’al, toupee…

Can best the literary world’s trompe l’oeil!

Tragedy

As the semester nears the finish line, deadlines are stressing me out. English majors are inundated with books to read, critical essays to evaluate (and in some cases decipher like cryptic code), and paper after paper to write. But I’m experiencing a bit of writer’s block. Even for this blog, which is a class assignment that I’ve come to enjoy.

These past two weeks have been emotionally trying. Last week, one of my TCNJ classmates went missing: Please read the linked story: Paige Aiello. Monday, two explosions turned a Boston tradition into a tragedy. Today, a Texas town was obliterated in an unintentional explosion at a fertilizer plant. Too much grief to process in such a short time.

So, while this blog post has nothing to do with Shakespeare, it does have to do with writing from the heart.

When I can return my focus to “all things Shakespeare,” I will blog about a wonderful experience I had this past weekend in Philadelphia.

But for now, the tears are clouding my screen, so I’ll close with a quote from a lesser known play, Henry VI:

“To weep is to make less the depth of grief.”

May tomorrow bring us respite from the tears.

“It is required you do awake your faith.”

I was hesitant to purchase a ticket for the opening night performance of Rebecca Taichman’s production of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale at McCarter Theatre in Princeton. Would the actors take the stage enthusiastically, or still be working out the kinks? But my initial concern was abated as the performance commenced.

Taichman opted for modern costuming, designed by David Zinn, and had the nine actors play two roles each: one as a character in Sicilia and the other as a Bohemian. This directorial decision tested the actors’ skill at drastically shifting persona and memorizing twice the dialogue.

I must say, they were all quite impressive, but Mark Harelik, who took on the roles of Leontes and Autolycus, was my favorite. Fans of the television series, “The Big Bang Theory” will recognize him as Dr. Gablehauser, the head of the Physics Department!

As in the text, the play opened in Leontes’ palace in Sicilia. The stage took on a somber hue with darker costumes and subdued lighting. Whenever Leontes had a soliloquy, the lighting would dim leaving a sole spotlight focused on Harelik, as a humming sound resonated in the background. This mimicked the disturbance in Leontes’ mood as jealousy took over his thoughts.

After intermission, the setting transformed from the iciness of the Sicilian palace in winter, to the lush pastoral backdrop, and vivid colors of spring, in the Bohemian countryside. Oversized butterflies and wooden sheep cutouts were carried onstage, as the lighting brightened.

The most spectacular scene of the play, however, is left intact and is Taichman’s directorial pièce de résistance: Act 5’s finale – the “statue of Hermione” scene. The curtain rises and Hermione, played by Hannah Yelland, is illuminated by a spotlight, as she stands completely still atop her pedestal.

When Paulina instructs Leontes: “It is required you do awake your faith,” and directs the small ensemble to play their music, Yelland slowly comes to life, as pendant lights dangling from above begin to sway. If for no other reason, I would recommend others to see this amusing production of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, as it wraps up its last week at McCarter Theatre, just to witness the beauty of this dazzling finale.

Happy Birthday, “Shake-speare!”

Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford, was born on April 12, 1550 at Castle Hedingham.

For those of us who dare to question the authorship of the Shakespeare canon, de Vere is the strongest candidate for the role. Those who align themselves with this scholarship are known as “Oxfordians.”

To learn more about Edward de Vere, check out the websites and blogs below:

“Shakespeare By Another Name,” Mark Anderson’s Blog

“Shake-Speare’s Bible,” Roger Stritmatter’s Blog

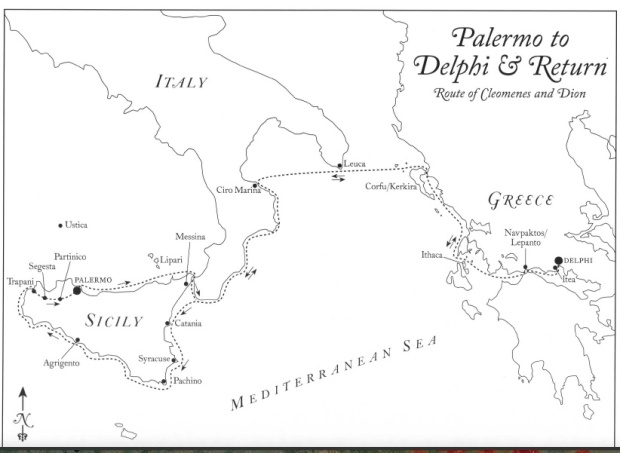

“Twenty-three days…” The Voyage of Cleomenes and Dion to Delphi (Part 2 of 2)

Continued from “Twenty-three days…” The Voyage of Cleomenes and Dion to Delphi (Part 1)

Continued from “Twenty-three days…” The Voyage of Cleomenes and Dion to Delphi (Part 1)

So, Cleomenes and Dion head off on their journey to summon the Oracle at Delphi for spiritual counsel on the matter of Hermione’s fate.

The map below comes from Richard P. Roe’s book, The Shakespeare Guide to Italy: Retracing the Bard’s Unknown Travels:

In Act 2 Scene 3, a servant notifies Leontes that “Cleomenes and Dion, / Being well arrived from Delphos, are both landed.” Leontes remarks: “Twenty-three days / They have been absent.” Why twenty-three days, you ask? Read the excerpt below from Roe’s intriguing book:

By the fact of specifically numbering the days of the messengers’ trip so exactly, Leontes’ words make us certain that the playwright knew about this route, having traveled it himself. And knowing the route, he also knew how long it took: ten days of sailing, three days at Delphi, then ten days back to Sicily and the royal palace: twenty-three days. Not fifteen or forty or twenty: exactly twenty-three. (Roe 254)

Roe then describes the method of sailing used by Mediterranean sailors: “coasting.” Mediterranean sailors did not sail throughout the night as did the English. They would travel close to the shoreline and “put in at nightfall safely near it, to eat and get a little sleep” (255).

So, if Shakespeare never set foot outside of England, how did he acquire this specific knowledge? Over a few pints with a seafarer at the Mermaid Tavern? Or, did the playwright actually spend time in Italy?

“Twenty-three days…” The Voyage of Cleomenes and Dion to Delphi (Part 1 of 2)

As promised in my previous post, “What geographical error?” I want to share with you another interesting excerpt from The Shakespeare Guide to Italy: Retracing the Bard’s Unknown Travels that relates to Shakespeare’s romantic play, The Winter’s Tale.

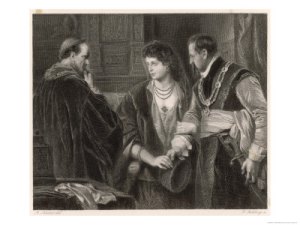

The Winter’s Tale, Leontes Nurses Suspicions of His Wife Hermione and Their Visitor Polixenes. Artist: M. Adamo

First, let’s set the scene: Leontes is certain, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that his wife, Hermione, has been unfaithful.

But he’s failed to convince the others in his court who sympathize with their queen.

So, to obtain “a greater confirmation” (2.1.180), Leontes sends two of his lords, Cleomenes and Dion, on a voyage to request spiritual counsel from the Oracle at Delphi.

In Ancient Greece, the Oracle at Delphi acted as a medium between Apollo and humans. She would channel answers to questions of great importance posed by Greek and foreign dignitaries.

In Ancient Greece, the Oracle at Delphi acted as a medium between Apollo and humans. She would channel answers to questions of great importance posed by Greek and foreign dignitaries.

Shakespeare requires that we suspend our disbelief, and imagine the Temple of Apollo as grand as it was in ancient times, rather than the ruins it would have been in the medieval setting of The Winter’s Tale.

To be continued…

What geographical error?

While scanning over various online lists of Shakespearean “facts,” I came across this interesting tidbit taken from “10 things you probably didn’t know about William Shakespeare:”

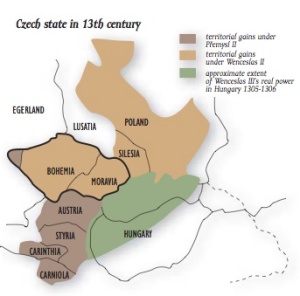

“4. Although Shakespeare wrote plays set in France, Scotland, Italy, Cyprus and Vienna, among many other locations, it’s entirely possible that he never left England. That may account for the most embarrassing geographical cock-up of his career: grafting a sea-coast on to land-locked Bohemia (part of the present-day Czech Republic) in The Winter’s Tale” (Times Online, April 9, 2009).

There is no evidence that William Shaksper/Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon ever set foot outside of Merry Ol’ England, therefore orthodox scholars typically excuse the playwright’s supposed lack of geographical knowledge. But, what if we were to learn that this alleged blooper was actually a true historical fact?

I decided to look into this purported “geographical error,” and referred to Chapter 11 of The Shakespeare Guide to Italy by Richard Paul Roe.

Research into the history of Bohemia reveals that the kingdom of Bohemia under the rule of Ottakar II once included Carinthia and “Carniola, which in turn touched the Adriatic Sea” (Roe 251). Therefore, from 1269 until Ottakar was killed in 1278, Bohemia was not landlocked.

The Winter’s Tale is a play that hearkens to the romantic tales of medieval times, so referring to the Bohemia of this period in history is not a stretch.

In my next post, I will discuss another curious detail in The Winter’s Tale that demonstrates the playwright’s uncanny knowledge of travel outside the boundaries of England.

In the meanwhile, check out the colorful scenic slideshow of the real-life settings of Shakespeare’s Italian Plays and retrace “The Bard’s Unknown Travels” in the linked blog post by Hilary Roe Metternich.